A Case for Livable Neighborhoods

Earlier this month, the UK government dismissed ’15-minute cities’ – an urban planning concept that reimagines neighborhoods as self-contained spaces, offering residents all they need, in a 15-minute radius on foot or by bicycle. With the government taking up cudgels on behalf of motorists, this seemingly innocuous idea has become a source of contestation worldwide. Nonetheless, the need for people-centered livable neighborhoods cannot be discounted.

Post the pandemic, cities around the world, such as Milan and Paris, began prioritizing livability by focusing on walking and cycling. In India too, the government is working to create public spaces through different initiatives. This is particularly important, considering India’s urban population of 377 million, according to census 2011, is further expected to grow to over 800 million by 2050 (UN DESA, 2014). Contemplating millions of new residents seeking basic services and opportunities is overwhelming. Instead, we could break this down – by looking at improving how we live, work and play – at the basic unit of a neighborhood. How livability, at the neighborhood scale, shapes up will determine India’s urbanization trajectory.

Neighborhoods are the physical construct within which our daily lives play out. A ‘Livable Neighborhood’ is the building block that ensures equitable access to services in a healthy environment. This also entails the creation of shared spaces that foster a sense of community – all housed within a resource envelope compatible with planetary boundaries.

While a broad transformation toward sustainable cities is ambitious, we can begin with people-oriented development and people-centric spatial planning at the neighborhood level. On-ground demonstrations have the potential to garner public support. This can create a ripple effect, building the city’s confidence in scaling up and even institutionalizing the prospect of livable neighborhoods as part of urban policies and planning.

This approach must take into consideration, people – particularly services such as housing, public transport and public spaces for vulnerable groups, nature – compact development models and resource efficiency that protects natural assets, and climate – interventions for building urban resilience and community adaptation capacities.

A people-centric approach to local-level urban development can transform neglected areas and create a strong sense of ownership, as seen in Kochi, where the Kawaki initiative sparked a science-based urban greening movement. This led to the mayor’s office earmarking a budget for scaling it up, while employing women for operations and maintenance of the natural infrastructure through the Ayyankali Mission, Kerala’s Urban Employment Guarantee Scheme.

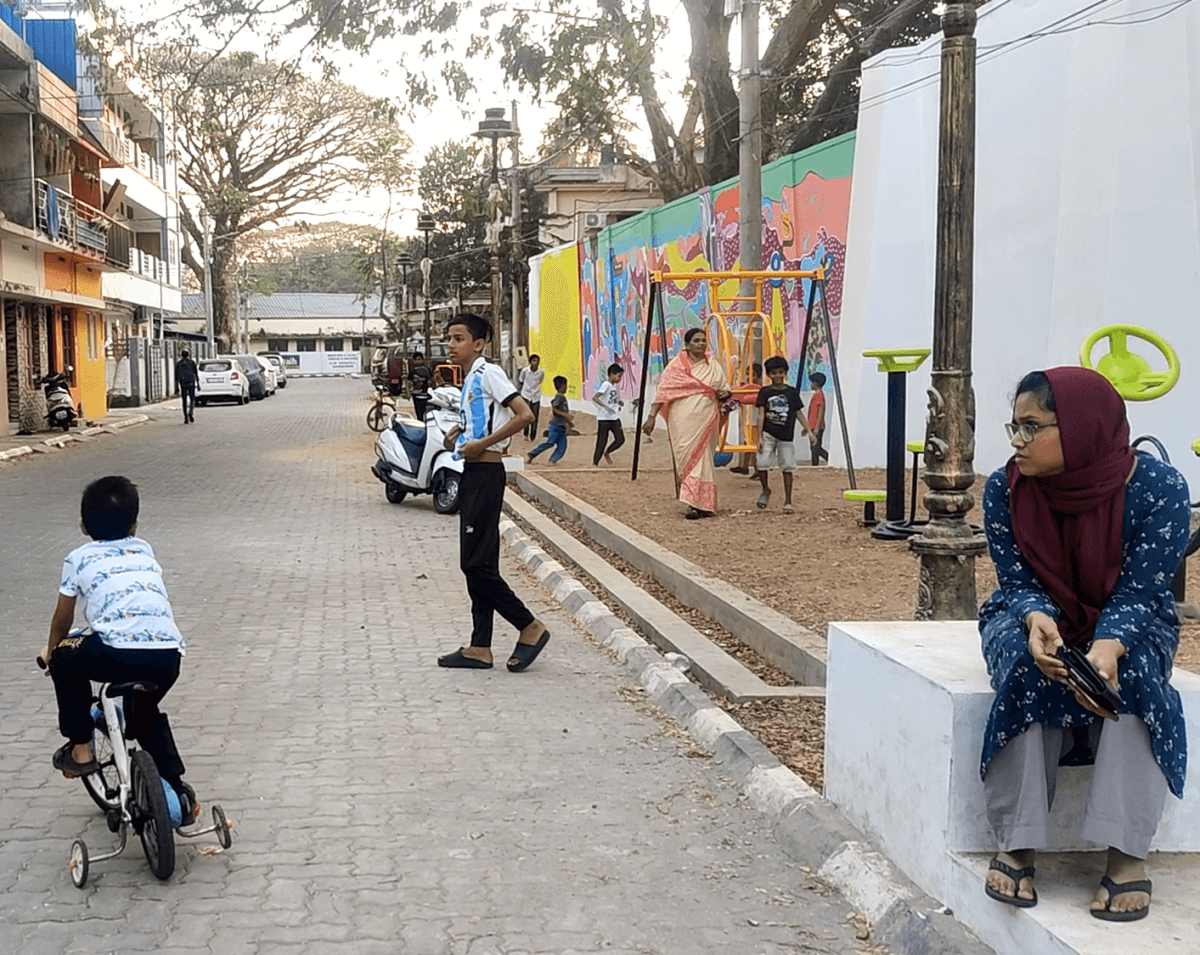

Other projects, such as the ‘Nurturing Neighbourhoods Challenge (NNC)’ led by the Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs (MoHUA), adopt a promising perspective by looking at cities from the lens of young children. NNC focuses on the needs of our cities’ youngest residents, and the people who care about them, and goes well beyond playgrounds. The 10 finalist cities have gone on to execute 150+ projects, laying the foundation for larger ecosystem behavior change. Many of these projects also fostered integration and equity in ways that some excluded communities had never experienced before.

One such transformational project was implemented in a leper’s colony in Rourkela. Separated from the rest of the community by a forbidding wall for over 30 years, the residents of the colony were largely shunned and stigmatized. NNC empowered city stakeholders to adopt a community co-creation process and a public park was created. Gradually, the neglected area around the park transformed into a vibrant community space.

This began drawing in children and adults from other neighboring areas, gradually leading to interactions that helped reduce prejudice against the community. The democratization of a simple urban feature – a public space – not only led to a better understanding of an otherwise excluded community but also instilled a sense of pride and dignity in residents of the colony.

While focusing on neighborhoods is vital, so is looking at their connectedness. Bengaluru, for example, will invest USD 7 billion over the next 12 years on the metro rail. The city is also working with different stakeholders to improve last-mile access, bring jobs and economic activity closer and strengthen resource-management strategies for the ecosystem integrity of the neighborhoods around the metro. Reimagining livable neighborhoods, in and around transit corridors, has the potential to leverage up to seven times the existing investment and economic opportunities, along with easing congestion and improving air quality.

Building sustainable cities, one neighborhood at a time, comes with its fair share of challenges and our cities have a long way to go before they become livable, especially, for the most vulnerable. Along with placing people, nature and climate firmly at the center, there are three major ways in which we can maximize impact. First, delivering an urbanization policy that prioritizes the tenets of livable neighborhoods and people-centered urbanization. Second, taking a multi-disciplinary systems approach to developing city plans and projects that promote coordinated urban development and strengthen governance. And third, communicating with and building the capacity of a diverse range of groups who have a stake in cities and their livability.

Today, more than half of the world’s population lives in cities, and nearly three-quarters will do so within our lifetimes. Our use of resources and our choices will not just shape urbanization but will determine the very future of our species on the planet.

All views expressed by the authors are personal.